Caravans of Hope:

Camels, Tea, and Entrepreneurs on the Silk Road

in the 21st Century

by

Randy Kritkausky, President of ECOLOGIA

November 8, 2009

Unbearable Myths

I recently flew to China over the North Pole. En route, I was struck by the melting and retreating ice sheets in Greenland and the open waters of a once permanently frozen Northwest Passage. I knew that, more than four miles below, the great white polar bear is struggling for survival and the prognosis is not optimistic. But despite growing evidence of the polar bear’s possible extinction in the wild, I found myself struggling with this climate change narrative.

As we headed further and further north and the seas remained open, I became less and less willing to allow the impending tragedy of the polar bear to become a prevailing narrative, or myth, about our planet’s future in a climate-change altered world. Myths sometimes disturb me, especially when they limit, rather than expand, our imaginations.

As the anthropologist Clifford Geertz noted, “myths” are powerful stories, real and imagined, that we tell ourselves about ourselves in order to understand ourselves and our world. I don’t want the polar bear to suffer the indignity of becoming the dominant climate change myth, quintessential climate change “victim”, or poster animal for fund raising. It would be the final tragic act of exploitation of this great animal by man. And it would be demoralizing to us, as humans. The polar bear’s demise should not become the only story we tell ourselves and our children, since it focuses on the hopelessness of our condition in a warming world. So, I arrived in China looking for hope. And I found the camel.

So, here is a tale about camels, Mr. Liu, the silk road, and the 2,000 year old story of tea in China.

Alternative Narratives and Realities

I will begin with Mr Liu. Liu Xiao Yong has a factory in the town of Bayanhot in Alashan Left Banner, Inner Mongolia. In order to understand Mr. Liu’s contributions to sustainable development, climate change adaptation, and desert protection you have to understand his business and its supply chain.

Mr Liu is a fiber processor. He owns an old factory that processes raw camel and cashmere fiber on well-worn combing machines. These machines, and the attentive workers who operate them, turn out to be an appropriate low tech, labor intensive solution for treating raw cashmere goat and camel fiber; it evokes the way respectful artisans process treasured fiber by hand. The fiber that Mr. Liu processes is first washed and cleaned. Then the coarse outer-hairs of camel and cashmere are carefully combed out on revolving drums and separated from the delicate and super fine under-hairs. The process is repeated several times; the final result is a pile of fiber as fluffy as a cloud.

Over the last several decades Mr. Liu’s factory has produced some of the world’s finest cashmere fiber, especially for the Italian market. It has even processed yak wool. It is fair to say that Mr. Liu and his factory have literally combed the international natural fiber market for solutions to the problems plaguing herders amid the great deserts of Inner Mongolia, where sand storms have become increasingly frequent.

Mr. Liu competes successfully with the giant, new, factories of the highly mechanized and overdeveloped cashmere and camel fiber industry, because his artisanal production yields unequaled quality; it does not weaken or damage fiber in a too-hasty effort to satisfy mass markets hungering for a cheap taste of cashmere, an effort at luxury that is the sartorial equivalent of a fast food chain hamburger.

While cashmere is the core of Mr. Liu’s business, he has a special affinity for camel fiber, considering it worthy of admiration equal to that of cashmere. Camel fiber provides a tactile experience to be enjoyed like good quality “slow food”. If you want to enjoy Mr. Liu’s newest offering in the camel fiber line, you may have to get off the well beaten highways of the global supply chain and travel some very dusty trails that are virtually unchanged since Marco Polo traveled them as part of a network of ancient trade routes that were first named the “Silk Road” by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen, in the nineteenth century. Although tea was often carried on the backs of humans who walked for hundreds of miles over the high mountain paths and passes into Tibet, camels were the major means of transport on the silk road.

The Alashan camel is uniquely suited to the extremes of Inner Mongolia and the Gobi desert. In a sand storm it can hunker down for days or weeks and survive without water or food. It can survive the most extreme heat and the most bitter cold. Since the camel is a highly adaptive survivor. Mr Liu wants to learn more about this animal; he would like scientists to study it in more depth, to understand how it can survive in such extremes.

I would like to nominate the Alashan camel to be the icon of animal and human adaptability in a warming world. But the Alashan camel is also more than that; it may be an emblem for a revived and sustainable Chinese economy rising from the dusty sands along the northern Silk Roads of Alashan and the foggy high mountain paths of western Sichuan. I must warn the reader that I have fallen in love with the camel. And like some pet owners, it appears that I have begun to look like my favorite animal.

Stitching Together New Solutions

Mr. Liu and his colleagues are creating a new product and assembling a supply chain, a virtual caravan of viable trade and sustainability. They are exporting rare treasures. This time, however, the Silk Road is to lead to a new destination, not across a continent, but within China. And it is not silk that is moving; it is camel fiber.

I discovered, through my most recent encounters with Mr. Liu, an alternative to endless struggle for dignity and economic viability in the often crushing global supply chain. I also learned that China does not always need, or want, to sell its treasures abroad. It does not need to transform unique resources into mass manufactured, unsustainable “China Price” commodities. There is an alternative that is better for China, its people and their environment. I tell this story, not intending it to be fodder for anti-globalization and anti- trade campaigners, but offering it as a reminder that economies, like ecosystems, benefit from diversity.

Mr. Liu is cooperating with the Alashan Camel Association to produce an added value product, a camel fiber stuffed quilt. Camel fiber is an undervalued commodity in the global marketplace. It is almost as soft as cashmere and is tawny brown, not pure white like cashmere. It is lightweight, and is ideal for people who are allergic or sensitive to wool. Camel fiber is virtually organic, though rarely certified as such. Camels graze in the wild and open desert far from modern pollution. They eat a “natural foods” diet and rarely if ever are exposed to feedstock or medicine.

Camels are also desert-friendly. Their large soft hooves are much less damaging to delicate desert ecosystems than are the sharp hooves of cashmere goats. Camels graze more gently than goats and sheep, who tend to stand in one place and chew plants to the ground. Camels are always moving; they roam up to 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) per day. They eat plants that would become invasive if left untended. Their grazing and pruning are essential to the balance of a complex desert ecosystem that ceased to be pristine and self-regulating centuries ago. Camels and camel herders are now part of the “natural balance” in Inner Mongolia’s deserts. Protecting both is the key to desert restoration and stopping dust-storms that plague people in Beijing and airports in Korea.

Two years ago I met Mr. Liu in his factory. We discussed the need to find a marketing solution that would encourage Alashan herders to emphasize camels rather than goats. I explained that our organization, ECOLOGIA, was working on a project to develop an international supply chain that would reward cashmere and goat herders for production strategies that preserved and restored the desert. We were thinking about a “fair trade” type of supply chain arrangement.

Just before my most recent trip, I heard that Mr. Liu had developed a new product, a camel fiber stuffed “quilt”. Technically speaking, the product is a comforter or “duvet”. Instead of being stuffed with goose down as is traditional in the west, it is filled with “baby camel fiber”. It is also filled with high hopes.

Mr. Liu wants to sell this product in the Chinese market at a luxury goods price. I was slow to pick up on his domestic marketing emphasis. Thinking within my own international marketing box, I thought we could “help” by finding an international buyer. But as I investigated this option, I quickly found out that international buyers add huge margins of profit and end up capturing the added value, much of which is used to pay rent and overhead in expensive urban retail stores.

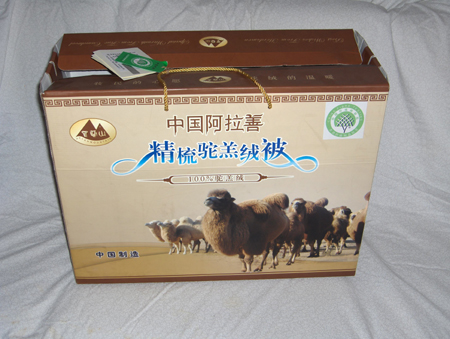

Camel quilt marketing with “HELANMOUNTAIN” trademark in upper left and “China Fibre Testing Ecological Textile” label in upper right. Box end reads “Alashan China Unique Quality Camelwool in the World” and “Noble Natural Fibre - Green Ecological and Environmental”.

So, Mr. Liu was patiently silent when I asked repeatedly what the wholesale price would be. Instead of offering a wholesale price, he informed me that his plan is to create and share the added value in China. Mr. Liu has seen, and painfully experienced, the once prosperous cashmere market distorted by giant cashmere combines that encouraged herders to overproduce, to switch to goats that produce more but lower quality fiber; he has witnessed the flooding and collapse of the market.

Camel fiber has not gone into this production cycle and is less susceptible to overproduction. And Mr. Liu intends to learn from, and avoid the mistakes of the past. So he took a few pages from our marketing and fair trade supply chain plan and re-configured our strategy. He contracted with camel herders to buy fiber above market rate, in exchange for their promise to reduce camel herds to more sustainable levels. He has offered a profit sharing and marketing plan that would allow herders to significantly increase their incomes. And he is marketing his comforters as an eco-friendly product.

I now envision a caravan of camels leaving the Alashan desert. On their backs are the attractive boxes Mr. Liu designed for his new product. The camels are heading south and east within the Chinese market.

In the upper corner of the box containing the camel quilts is a new product trademark, Helan Mountain. This mountain is sacred, the home of ancient rock paintings, a high peak in the range of mountains creating Inner Mongolia’s eastern border.

More Mountain Branding and Added Value on the Southern “Silk Road” in Sichuan Province

Chengdu is famous for, and full of, tea houses. These are places to relax with friends, or to hold a quiet business meeting. Yang Qi’s office tea house, the headquarters of his Zhi Ju Si tea company, is more than just another tea house. It is a portal into China’s past and its future, where the present becomes a shrinking point in time suspended between history and hope.

Yang Qi welcomes visitors to his office and prototype tea house on the second floor of an old style Chengdu building. He wears traditional, not business, clothing. Visitors are seated around a massive wooden table carved from a single tree trunk. And the ritual begins.

Hot water is poured into delicate green crackle glaze celadon cups held by wooden tongs. The water runs across the cup to warm it, onto the table surface, across its expanse and through a series of channels away and out of site. The process is repeated with the tea itself. The leaves are moistened and the first batch of tea is poured over small wooden animals on the table. This first tea is a gift to the spirits of prosperity and happiness. The process is repeated and the second cup of tea is readied.

Yang Qi’s graceful swirling hand motions are mesmerizing; his narrative is transporting. This is a man in love with tea and its past. He collects and reads ancient texts looking for information on tea: tea plants, tea processing, tea rituals. Yang Qi has rescued teas from the oblivion of time. He serves us one tea, a favorite during the Tang Dynasty. He believes this tea has not been prepared and offered for centuries. I am an admirer of Tang Dynasty ceramics. Their graceful and powerful lines almost explode with energy; their yellow, green and brown glazes have never been surpassed for simple earthy beauty. Now for the first time I am tasting the Tang dynasty. It is intoxicating. In fact, I begin to feel, or think I am feeling, light headed. So I ask Yang Qi if the tea can cause such a sensation. He explains that fresh good tea causes the blood vessels to open, and at first the cheeks and face tingle. Then there is a slight sense of “tea intoxication” all over. This might be missed in a less quiet and more busy environment, but not in Yang Qi’s tea house.

In the background traditional music fills the air. When I ask about it, Yang Qi informs me that he and some friends commissioned a group of musicians to make the recordings. It is a non-commercial venture involving an agreement not to reproduce or sell the music as a commodity. The music is an experience to be shared like tea. It is a Chinese treasure for use within a community of friends. I hear echoes of Mr. Liu’s explanation of his desire to keep his camel comforters within the Chinese market. And I am deeply moved when Yang Qi offers to put the music on a memory stick so I can have it on my lap top and play it for my friends.

Yang Qi is an entrepreneur, though certainly not a conventional one. His aspirations reach further than those of a “social entrepreneur” who seeks to use a business model as a vehicle to address social needs. Yang Qi thinks about business, but he thinks first about cultural preservation. I would call him a social capitalist: an individual who expends wealth to create social capital. Yang Qi wants to preserve and elevate tea culture and restore tea consumption to its life enriching status, one that incidentally brings out the real flavor of tea. His business plan is to create tea houses where there are different dynastic tea rooms serving teas of the period in appropriate historical and decorative settings. This is probably a very good business plan in newly affluent China, and it may well succeed.

But success for Yang Qi will not only be measured in terms of profits; it will be measured heavily, or even primarily, in terms of social-cultural impact. This subtle shift toward producing a public good rather than private goods might be easily missed when first talking with Yang Qi. Outsiders might even perceive Yang Qi as letting potentially profitable business opportunities slip through his fingers. In fact, he is deftly flipping business distractions aside, when they do not fit within his social capital mission.

Misreading the hierarchy of Yang Qi’s priorities would be to misunderstand Yang Qi and a new kind of Chinese “entreperenur” who feels himself or herself to be part of a trans-generational social-historical enterprise. Putting Yang Qi into a traditional entrepreneur or business model box would be like categorizing Michelangelo as a businessman as opposed to an artist because he also negotiated his fees. It is hard to grasp the logic of this when reading a report some thousands of miles away. You have to stand in the mists of the Mengshan mountains, where Yang Qi’s tea culture is rooted, and visit its temples to understand what is truly at stake. So we make plans to drive west into the mountains the next morning and visit the place where tea originated.

The Mengshan mountain peaks rise to 1546 meters above the Sichuan basin. They are normally shrouded in fog and rain clouds, which moisten the steep terraced slopes. This moisture, combined with suitable soil, temperature, and elevation make the mountains ideal for tea production. This is undoubtedly why tea was first domesticated here more than two millennia ago.

Wu Lizhen is credited, by legend, with first planting or domesticating wild tea in the Mengshan mountains in 53 BCE, when he planted seven tea bushes on top of the highest mountain peak. By the eighth century, tea from the area was designated as one of the annual items of tribute to be paid to the Emperor. For centuries afterward, Buddhist monks gathered tea, supervised tea production, and monitored delivery to the Emperor. Today the area brands its production as “Emperor Tea”. Many of the ancient Buddhist monasteries associated with tea production still stand; a few are active.

When Yang Qi purchased a small bankrupt tea factory and tea house resort in 2001, he discovered that a Buddhist temple to Wu Lizhen lay within the compound. The temple has seen many changes over the centuries; its statues and architecture have periodically been altered and recreated. But much of the building remains intact. Most certainly its spirit survives. The temple is recognized as the central place of worship for Wu Lizhen, the patron saint of China’s tea industry.

Temple to Wu Lizhen, Mengshan Mountain, Sichuan Province

The second floor of the temple is a tea museum with enlarged photographs of historical documents relating to the temple. Parts of the walls are made of aging tea bricks, filling the room with a tea scent. The tea is aging, much as wine does in the cellars of French chateaux. It will be ready in twenty or thirty years. By that time it will have been fermented by ambient micro-organisms. It will have breathed and absorbed the local air. And as our host implies, it will have absorbed something of the atmosphere of a sacred place, an ingredient few other teas can offer.

Dignitaries and tourists, mostly Chinese from near-by Chengdu, frequent Mengshan mountain tea houses in the spring and summer. Yang Qi’s tea house resort is a prominent destination point because of its association with Wu Lizhen. If Yang Qi has his way, his temple compound will be the epicenter of a regional branding tide that will lift all boats, not just Yang Qi’s Zhi Ju Si tea brand.

The Whole Supply Chain Can Be Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts

Yang Qi’s neighbors just down the mountain are in some ways a more accessible and understandable business model for westerners. A new cooperative of tea farmers, and a family artisanal tea processing business, are part of a potential new model of producing and marketing tea in Sichuan.

Lin Geng Tea House, operated by Gao Zhong Wei, is a family operation: two generations of tea growers and processors. Gao Dian Fu, the son, just founded a tea growers cooperative combining nearly a hundred households that produce tea grown with minimal use of chemicals. Members of the cooperative are young and willing to be innovative. Some have begun to produce a more traditional variety of smaller and more flavorful tea leaves. They attended a workshop on organic agriculture that ECOLOGIA sponsored, and are seriously interested in making the leap from low chemical intensity tea production to certified organic production. This is undoubtedly because they have already tasted the benefits of producing and marketing “greener” green tea.

Much to our surprise, we found here something akin to what is known in Vermont as “Community Supported Agriculture”. Lin Geng Tea House has been selling most of its processed tea and a small segment of total local tea production directly to Chengdu families who subscribe to annual tea purchases. The families come out to the tea house-factory where they can see the tea being processed in small hand-roasted batches. They can meet the farmers who use low-chemical intensity methods of growing. And they pay a premium. As a result, tea growers get a 4-6 Yuan per kilogram premium for their product and the family tea processing business makes a comfortable annual profit.

With an annual total processing capacity of only 800 kilograms (1,763 pounds) of tea, both the Lin Geng Tea house and the farmers’ cooperative face problems of scale. If they increase their scale they risk losing their artisanal status and quality control. However, there are hints of opportunity for marketing a new even higher end tea product. Some of the artisanal tea produced at the Lin Geng Tae House, when packaged more attractively, brings as much as 1000 yuan per kilo. This is double the conventional “bulk” rate. Combining traditional smaller leaf tea, organic production, improved packaging, and Yang Qi’s regional branding initiative could result in a transformation of the Mengshan tea industry.

Yang Qi’s Zhi Ju Fangi tea branding presentation using

imperial yellow, dragon motifs and ceramics.

New and Old Peaks in Branding

Mr. Liu and the camel herders of Alashan use Helan Mountain as their brand and trade mark. Yang Qi and the tea farmers of Sichuan use Mengshan Mountain to brand their tea. This new added value business model could transform regions listed as impoverished in China’s national census. Both regions are finding solutions for economic, social and environmental problems. They are using traditional products and exploring modern marketing to plot a path to a more sustainable future.

Niche marketing will certainly not solve all of China’s development needs. But the undercurrent of pride and self-confidence, combined with an ingenuity that addresses environmental and social problems, could be the turning point in a business culture that has over-emphasized mass production at dangerously marginal “China Price” profit margins.

|